Learning Literacy Together

Home-based learning was implemented in all schools and institutes of higher learning from April 8 to May 4, as part of tighter measures against COVID-19. Apart from technical issues and ensuring all students had sufficient digital access, there were concerns over how the quality of learning would be impacted. Research has shown that online lessons tend to be less effective than physical ones, one reason being the difference in learning environments. In particular, students who require more academic support may generally find it harder to thrive in digital lessons.

To support these students, Heartware Network rolled out the Learning Together Programme (LTP), which aims to provide learning support for vulnerable students at the lower primary level to improve their literacy skills. The literacy skills taught include vocabulary, narrative skills and phonological awareness.

Volunteers help to augment the efforts of participating primary schools by reinforcing the students’ learning through online reading sessions. They engage the students in one-on-one lessons, which can last up to 30 minutes and occur thrice a week.

To find out more about the LTP experience, three volunteers were interviewed, sharing their involvement so far.

Ching Hwee, 17, has been in this programme for about a month, having conducted more than ten sessions. To fulfil the service requirements for her IB Diploma, she signed up for LTP, finding the commitment level manageable. But that was not her only motivation.

“This opportunity arose during the Circuit Breaker, so it was actually very timely … I was starting to feel a little stagnated in life,” Ching Hwee admits, “Besides school, I felt like I should do something to grow.”

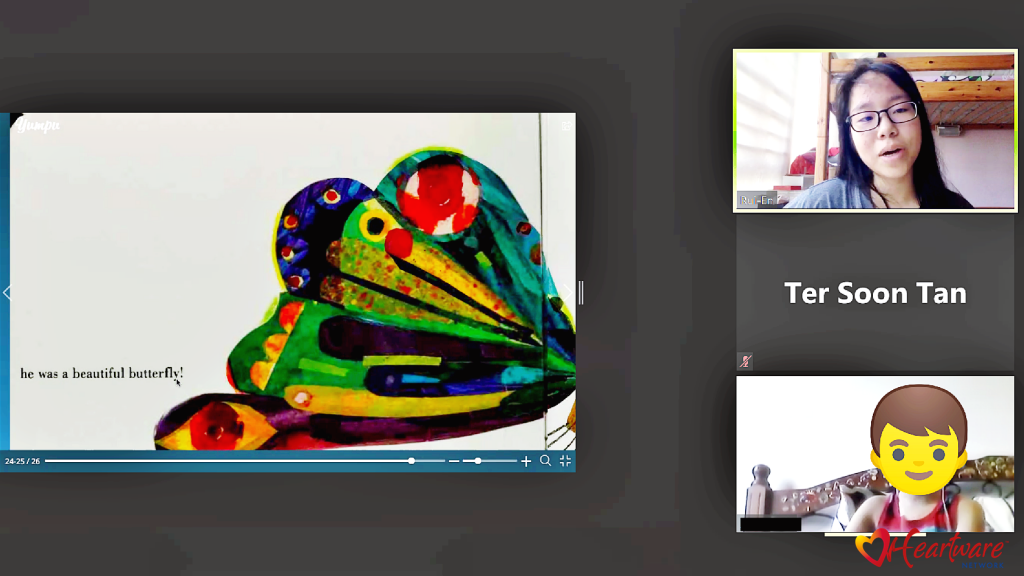

Her buddy, Max*, is a boisterous boy who actively participates in LTP. The lessons generally involve reading aloud and spelling, geared towards improving grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation. The lesson structure and materials are prepared by the volunteers, who underwent a 2.5-hour training to learn what to expect and how lessons could be conducted.

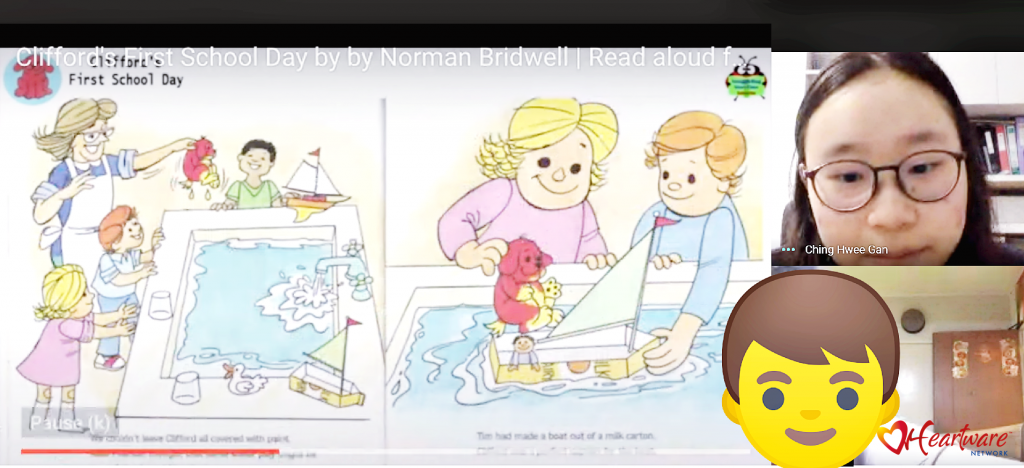

Ching Hwee and Max reading ‘Clifford’s First School Day’, which Max greatly enjoyed. He even requested to extend the session for an extra 15 minutes to finish reading it!

Ching Hwee initially used materials from the recommended resource pack, but quickly found them to be unsuitable for Max. As he attended sessions on a phone, the words displayed in the storytelling videos were too small, making it tedious to read. He was also daunted by the difficulty of some stories. These problems led to Max struggling to read and becoming disinterested for the first few sessions.

Deciding that a change of pace was needed, Ching Hwee took inspiration from what she enjoyed reading as a child, and introduced the series Clifford the Big Red Dog to the lessons. She quickly found that the Clifford series was perfect for Max. He greatly enjoyed it, even requesting her to read the stories to him again. Relying on her own reading experiences turned out to be a good teaching strategy! She shares: “[The series] was super vivid! I can remember reading it over and over again. And it’s not too difficult.”

Given the online mode of learning, Ching Hwee had to come up with ways to enhance the learning experience. For instance, to make reading more comfortable for Max, she took screenshots of the storytelling videos and organised them into slides so the words were larger and more readable. She would also prepare beforehand numerous pictures from Google Images to support his understanding of potentially difficult words.

During the sessions, Max reads aloud diligently. His pronunciation is not perfect, but it is heartening that he tries reading even the unfamiliar words. For such tricky sentences, Ching Hwee would enunciate them slowly, before getting him to try once more. Most of the time, he gets it right after a try or two. But he still struggles to master some words. While he can get frustrated after several unsuccessful tries, Ching Hwee is patient, asking him to try again in the next session.

Throughout the lessons, snippets of casual conversation can be heard between the two, pointing to Max’s communicative attitude. He was not always so open though. “[The change] was very progressive,” Ching Hwee reveals, “[In the first session], he kept to himself a lot. When he didn’t know the words he didn’t ask, even though I told him to.”

Now, his confidence has clearly shot up as the pair become more familiar with each other. While some of his behaviours can be disruptive at times, such as spamming the chat function, Ching Hwee would take his outgoing and spontaneous self over a reserved attitude any day. Working with withdrawn children can be more challenging as their reluctance to participate can hinder the lessons, and their reticence can mask their academic ability and learning needs. This is a concern shared by other LTP volunteers.

Ruben is very patient with his buddy John*, doing his best to explain the meaning of words in a simple manner, such as through visual demonstrations and antonyms.

Ruben, 17, shares his initial worries: “I remember thinking, ‘What if the child doesn’t want to do anything? What if he doesn’t want to read?’” Nevertheless, he was prepared to do his best to break the ice if his buddy turned out to be shy.

In the first session, Ruben spent time getting to know more about John*. When he found out that John enjoyed football, he knew he had his break. “The moment he said [he liked] football, it just clicked, because I also watch football a lot. After that, we just started talking about players and the different leagues,” Ruben laughs, “To be honest, he knows more than me.” Like Max, after the first few sessions, John became more enthusiastic in the lessons, demonstrating a desire to learn more.

While Ruben and John have built up a close bond after numerous sessions, Ruben would prefer to teach in a physical setting, because they feel more personal. They could also be more effective given the better learning environment.

Rui-En, 17, who has been volunteering for two months, shares a similar sentiment, preferring face-to-face lessons as it would be easier to engage her buddy, David*. Home environments may not always be conducive for learning due to many possible distractions. For instance, on some occasions, David playfully dashed off in the middle of reading to find something interesting to show Rui-En. Learning at home may sometimes also end up being a learning crutch for some children as they can turn to their families when they encounter difficulties.

Rui-En reading “Three Billy Goats Gruff” with David. Once they were done reading, David ran off for a moment, reappearing to show Rui-En his exercise ball.

Rui-En recalls with amusement, “At the start, for every single question I asked, he would turn to his mum and look at her [for help]. The funny thing was that he was wearing earphones, so his mum could not hear what I asked. She would look back at him, like ‘What?’ and there would be an awkward silence for a few seconds. She would then take the earphones and [help him with answering the questions].” Fortunately, having grown more comfortable with the online lessons, David now responds to most questions independently, seeking his mum’s guidance only on those he does not understand.

In the end, while the online sessions can present some challenges for the LTP volunteers, they are not insurmountable. Problems such as children being unused to the online learning format, or getting distracted by their home environment prove to be temporary as more sessions are taught. “Even though there have been some difficulties, they aren’t much of a problem. They are really just small, minor setbacks,” Rui-En shares.

Whatever the lesson format, the volunteers all hope to see their buddies come out of the LTP with improved literacy. They hope their buddies will be able to read independently and remember the new words they have learnt.

The children are not the only ones that have grown throughout the LTP. Ching Hwee shares an insightful takeaway: “[I learnt that] my energy levels are very contagious. … As Max was quite shy at the start, I tried to be more energetic in hopes that … he would be able to exude that kind of energy.”

For Ruben, he believes that having the right mind-set matters. Being positive towards the child’s mistakes is part of it. In the first session, he had sensed that John wanted to give up reading, as the book was too difficult. However, Ruben remained patient, reassuring John and even setting a goal with him to master the book by the end of LTP. “The moment you get negative, they can get easily demoralised,” he remarked.

For youths who are keen on being an LTP volunteer but may be worried, do not be! There is a first time for everything after all, so some trial-and-error would be necessary. Rui-En shares some advice: “In any volunteering [activity], the person on the receiving end will feel a difference if you are not passionate.”

“You need to be passionate about what you are doing.”

—

*Buddies’ names have been changed to protect their privacy.